- Home

- Patrick W. Galbraith

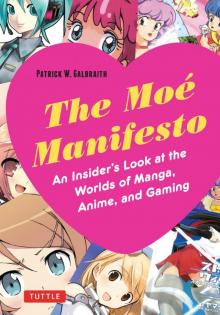

The Moé Manifesto

The Moé Manifesto Read online

Patrick W. Galbraith

The Moé

Manifesto

T UT T L E Publishing

Tokyo Rutland, Vermont Singapore

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 1

13/2/14 10:01 AM

Contents

4 Introduction

24 ITO KIMIO

From Social Movements to

Shojo Manga

30 KOTANI MARI

Memories of Youth

38 OTSUKA EIJI

From Shojo Manga to Bishojo Magazines NDA LLY

46 SATO TOSHIHIKO

On Magical Girls and Male Fans (Part One)

/FRIENDOC

ZE©

YA

54 NUNOKAWA YUJI

5 On Magical Girls and Male Fans

THWA

(Part Two)

HN

JOH©

64 POP

6 Talking about Moé at the Heart

of Akihabara

72 MOMOI HALKO

7 The Voice of Moé Asks

for Understanding

80 TOROMI

8 Notes from Underground

90 SHIMADA HUMIKANE

9 Bridging the Gap between

Mecha and Moé

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 2

13/2/14 10:01 AM

98 MAEDA JUN

The Crying Game

108 ITO NOIZI

Girl Drawing Girl

116 HONDA TORU

The Love Revolution Is Here

126 MORINAGA TAKURO

For Love or Money

136 HIGASHIMURA HIKARU

The Moé Studies Research Circle

144 SODA MITSURU

The Philomoé Association

152 MORIKAWA KA’ICHIRO

Learning from Akihabara

162 ITO GO

The Pleasure of Lines

T

170 AZUMA HIROKI

Applying Pressure to

INMEN

TA

the Moé Points

ERT

ENL

ITA

IG

N

D

WO

MI

L

178 SAITO TAMAKI

Otaku Sexuality

A

G

N

C

O K

MN

©

OM

186 Glossary

RAY B

PH

188 Index

RAGOTO

PH

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 3

13/2/14 10:01 AM

4

Falling in Love with

Japanese Characters

“Are you familiar with Japanese moé relationships, where socially dysfunctional men develop deep

emotional attachments to body pillows with

women painted on them?” asks James Franco, guest starring on the NBC sitcom 30 Rock in January 2010. Later in the episode, the actor is shown holding a pillow with an anime girl crudely drawn on it. Franco calls her Kimiko. Viewers cannot suppress their laughter.

The laughter comes from a growing worldwide awareness of Japanese popular culture, including the antics of some of the more extreme fans of manga, anime, and games. Just as anime and manga are understood to be distinct from cartoons and comics, fans of anime and manga are in a category of their own: otaku. While talking about moé, Franco offers a concise description of otaku: “socially dysfunctional men”

who are entirely too attached to fi ctional girl characters.

From where did the writers of 30 Rock get this idea? Perhaps a July 2009 article in the New York Times that describes “moé relationships” with body pillows as a social phenomenon in Japan. Given the prevalence of such articles in the popular press, many watching 30 Rock shook their heads, smiled, and thought, “Yes, James Franco, we know moé!”

But what does moé even mean? The 30 Rock viewer sees a man with a body pillow, which he seems to love. Is that moé?

THE MOE

´ MANIFESTO

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 4

13/2/14 10:01 AM

5

Used as part of an inside joke, it seems that

that

everyone implicitly understands moé—it

t

needs no explanation. James Franco holds

ds

aloft exhibit A. He says it’s a Japanese

thing. We know they’re weird, right? Case

se

closed.

In order to formulate an independent

opinion about moé, we need some defi nitions tions

and context. Linguistically speaking, moé (

é 萌え

(

)

萌え)

is the noun form of the verb moeru, meaning to ning to

burst into bud or to sprout. There is a youth-

uth-

ful vitality to the word, refl ected in its use in

se in

Japanese poetry from as early as the eighth

hth

century. Moé can also be a given name,

which in manga, anime, and games is typ-

p-

ically reserved for young girls. The word

is pronounced moé (i.e., with the fi nal “e”

”

sound stressed separately as “eh”).

In the 1990s, otaku gathering online

to talk about manga and anime char-

acters began to use the word moé as slang

ng

for burning passion. The story goes that

they were trying to write the verb moeru (燃

(

える), “to burn,” but computers would often

ten

mistakenly convert this as the homonymous

mous

Y

verb moeru (萌える), “to burst into bud.”

E

In this contemporary usage, moé means an af-ns an af-

T’S / K

fectionate response to fi ctional characters.

r

s. There

Ther

AL ARUIS

are three things to note about this defi nition.

iti

on. First,

Fi

rst,

moé is a response, a verb, something that is done t i

.

s done

.

© 2004 V

Second, as a response, moé is situated in those those

Moé: an affectionate response

to fi ctional characters

INTRODUCTION

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 5

13/2/14 10:01 AM

6

responding to a char-

NWOL

acter, not the character

GC

M

itself. Third, the response

NOM

is triggered by fi ctional

RAY B

characters.

PHS

RA

The characters that

GOTO

trigger a moé response,

PH

sometimes called moé

characters ( moé kyara), are

most often from manga,

anime, and games. Materi-

al representations of char-

acters—fi gurines, body

pillows with the charac-

ter image on them—can

trigger moé. Sounds and

voices are described as

Figurines can trigger a

moé response

THE MOE

´ MANIFESTO

&nb

sp; MOE_FM_1-23.indd 6

13/2/14 10:02 AM

7

moé when associated with characters. A human can trigger moé when dressed in character costume, just as an object can be anthropomorphized into a moé character. What is important here is that the response isn’t to the material object, sound, costume or person, but rather to the character.

To return to our defi nition, moé is a response to fi ctional characters, and when we talk about moé we are necessarily also talking about how people interact with fi ctional characters.

Available evidence suggests that interacting with a character in a manga, anime, or game, one can become signifi cantly attached to that character. Indeed, some otaku describe such attachment in terms of “marriage.” This can be as casual as calling a favorite character “my wife” ( ore no yome) or as serious as announcing a long-term, committed relationship.

Author and cultural critic Honda Toru, for example, has said that he is married to Kawana Misaki, a blind high-school girl from the game One: kagayaku kisetsu e (1998). A shy man, Honda is also something of a radical who advocates moé relationships in books he has written, for example No’nai ren’ai no susume (Recommending imaginary love), published in 2007.

Many have followed in Honda’s footsteps. On October 22, 2008, a man called Takashita Taichi set up an online petition asking the Japanese government to legally recognize marriage to fi ctional characters. Within a week, a thousand people had signed it. On November 22, 2009, a man calling himself Sal 9000 married a character from the game LovePlus (2009) in an offi cial-looking ceremony held in Tokyo. “I love this character,” the man told CNN. “I understand very well that I cannot marry her physically or legally.” Remember James Franco’s body pillow? Well, on March 11, 2010, a Ko-rean man announced his marriage to the character drawn on his body pillow.

INTRODUCTION

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 7

13/2/14 10:02 AM

8

On the one hand, these marriages are playful performances by otaku that we perhaps shouldn’t take too seriously.

On the other hand, however, these marriages do signifi cant work. As anthropologist Ian Condry sees it, otaku are demonstrating their devotion to others in a political move to gain acceptance of attachment to fi ctional characters. These public declarations of love for fi ctional characters pose important challenges to accepted norms. Honda Toru calls the awakening to moé relationships a “love revolution” ( ren’ai kakumei), which entails the embrace of fi ctional characters and libera-tion from oppressive social and gender norms. For the record, Honda doesn’t care about legal recognition of his marriage, because he refuses the authority of institutions that he sees as corrupt to legitimize his love.

To understand moé, we need to consider how it is possible to become attached to the characters of manga and anime in the fi rst place. Comparisons to comics and cartoons risk grossly misrepresenting the status of manga and anime, which are vibrant forms of mass media in Japan. Consider Tezuka Osamu’s Astro Boy (1963–1966), which in 1963 was adapted from a popular manga series into a weekly TV serial, had product tie-ins and sponsors, spin-off merchandise and toys. Media researcher Marc Steinberg argues that this became the basic model for character franchising in Japan, which is now ubiquitous. Encountered constantly in this pervasive way, characters are a very real and intimate part of everyday life in Japan.

As psychiatrist Saito Tamaki sees it, fi ctional characters can become the object of romantic love for those growing up with them. One’s fi rst love can just as easily be a manga character as it can be an idol singer on TV or a girl in your class. When I fi rst met Saito, I was a little shocked by how easily those words rolled off his tongue. I pressed him on THE MOE

´ MANIFESTO

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 8

13/2/14 10:02 AM

9

Astro Boy

how normal it is to fall in love

with fi ctional characters, and

he turned the question around

on me. “Why is it strange to

love manga characters?” I re-

call the scene vividly even now,

because it revealed to me how

differently characters are regarded

in Japan, where there is such an all-

pervading manga and anime culture

compared to the United States.

The roots of moé go deeper than

S

many suspect. Helen McCarthy,

TION

author of a number of reference

RODUC

books on manga and anime,

P

notes similarities between

EZUKA T©

the postwar manga of

INTRODUCTION

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 9

13/2/14 10:02 AM

10

Lost World (1948), Tezuka Osamu

S

TION

RODUC P

Tezuka Osamu and contemporary offerings. McCarthy zeros in on Tezuka’s Lost World (1948), in which a scientist in an EZUKA T©

alien world has developed a method of genetically engineer-ing females from plant matter. The scientist intends to sell the plant women as slaves, and his prototypes are made attractive to tempt potential buyers. Another scientist on the planet befriends one of the plant women, Ayame. Later, the two are left stranded in the alien world and decide to live as

“brother and sister.” As McCarthy writes on her blog, “This is essential moé —an innocent, literally budding girl, a geeky young man with the heart of a hero and protective instincts to do any father proud.”

THE MOE

´ MANIFESTO

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 10

13/2/14 10:02 AM

11

While largely agreeing with McCarthy’s analysis, Meiji University professor Morikawa Ka’ichiro points out the physical attractiveness of Ayame, which, he argues, was extremely stimulating for young male readers. Many early postwar manga artists in Japan list Lost World as a major infl uence.

In this sense, says Morikawa, Tezuka could be considered to have sown the seeds of moé culture.

Among the fi rst to respond to Tezuka’s work by making explicit the attractiveness of his characters was the manga artist Azuma Hideo. In the late 1970s, Azuma combined the rounded character bodies associated with Tezuka’s manga with the expressive character faces associated with shojo manga (manga for girls),

which resulted in a hybrid

form known as the bishojo,

meaning cute girl.

Fans of bishojo charac-

ters were among those

manga and anime enthu-

siasts fi rst labeled otaku.

The columnist Nakamori

Akio, writing in the sub-

OE

ID

cultural magazine Manga

MA HU

Burikko in 1983, used the

© AZ

word otaku to mean some-

thing like geek or loser.

Azuma Hideo is named

explicitly in Nakamori’s

articles about otaku, and

those attracted and at-

tached to bishojo are called

all sorts of names in ad-

dition to otaku—including Azuma Hideo’s “cute girl”

INTRODUCTION

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 11

13/2/14 10:02 AM

12

E

LE

EW

DR N AYS

TE R

COU OT

HO P

THE MOE

´ MANIFESTO

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 12

13/2/14 10:02 AM

13

leeches and slugs! The ferociousness of Nakamori’s reaction refl ects a more general discomfort with the ways men were interacting with bishojo characters. Cultural critic Takekuma Kentaro recalls being shocked and dismayed at the increasing popularity o

f bishojo manga, even as manga editor Sasakibara Go and sociologist Yoshimoto Taimatsu point to the late 1970s as a crucial time of “value changes” ( kachi tenkan) among Japanese fans.

The years 1978 and 1979 are crucial. Famed creator Miyazaki Hayao gave his fans two female characters—Lana, from the TV anime Future Boy Conan (1978), and Clarisse, from the animated fi lm The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)—and they g

y gained an incredible following. As journalist Takatsuki Yasushi writes in

his book, Lolicon: Nihon no

shojo shikoshatachi to sono

sekai (Lolita complex: Ja-

pan’s girl lovers and their

world), published in 2010,

fanzines about Clarisse

IAIWAAWA were abundant enough to

K KU KZUAZA have their own category:

KOIRROK Clarisse magazines ( kura-

D HDH

AR

risu magajin). Also in 1979,

OWH

SY HSY

Azuma Hideo and friends

ETRUUR published the fi rst volume

O

TO COC

of the legendary fanzine

OHPPH Cybele, which stressed a

cute aesthetic over real-

ism and opened the eyes of

many fans to the charms of

bishojo characters.

Gundam

Gun

fanzines

INTRODUCTION

MOE_FM_1-23.indd 13

13/2/14 10:02 AM

14

Further, in 1979, the anime series Mobile Suit Gundam aired on Japanese TV. Often considered a “realistic robot” anime, and much loved by mecha fans outside Japan, the series was at fi rst heavily criticized by established sci-fi fans inside Japan, who were dismissive of the melodramatic emphasis on human relationships and scathing about the shallowness and excitability of fans of the series. Though it is not much remembered today, news reports from the time detail how Gundam fans would dress up as characters from the series and make a spectacle of themselves on the streets of Hara-juku, one of the epicenters of Tokyo’s youth culture. Fans of Mobile Suit Gundam have long peppered their fanzines, which are at least ostensibly about robots, with images of cute girls.

The Moé Manifesto

The Moé Manifesto